wu-tang clan, $4 million dollars, and a phone booth

music as law as code as art

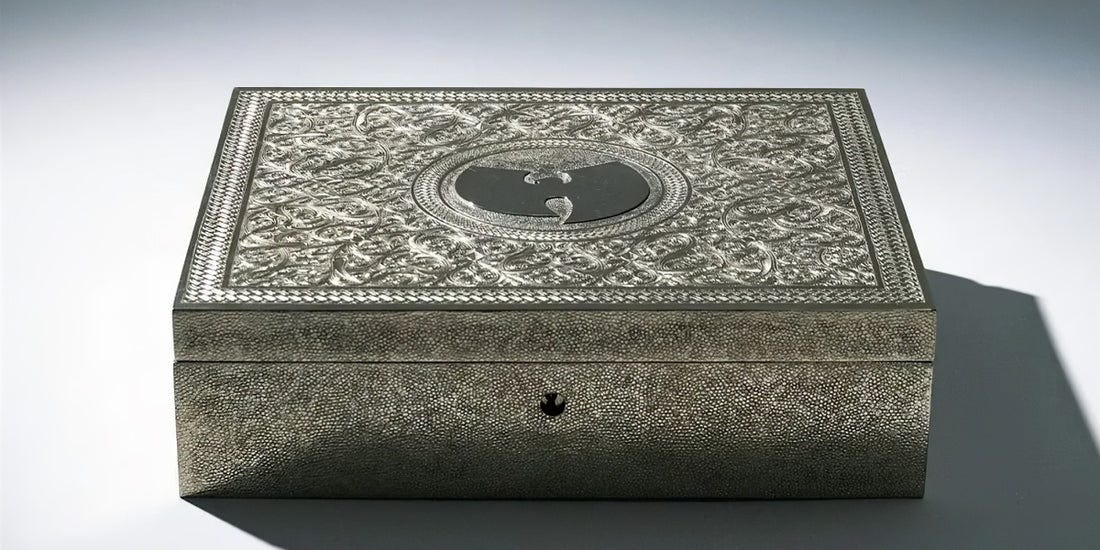

There’s a Wu-Tang Clan album sealed in a silver box that legally can’t be streamed until the year 2103.

One copy. One owner. One contract that forbids commercial use, reproduction, or broad public performance for 88 years.

We were given this album, and one impossible prompt: make some art out of it.

Fortunately, this wasn’t my first rodeo in legal gray areas – or in the strange polyamorous marriage of music, technology, and law. I spent my youth dialing through 56K modems pirating half the internet – Napster, Soulseek, BitTorrent, you name it, I used it to download music.

Since then, I’ve learned (at least) two things about music: it’s always a little bit illegal, and illegal is a sick bird.

(ill eagle...okay, okay, I’m sorry.)

1.0 Music as Law

One constant in the music industry is that every era invents its own sonic contraband. Bootleg cassettes. Dubbed CDs. Limewire zips. YouTube rips. SoundCloud remixes. AI voice models. Whatever the medium, the pattern repeats: artists innovate, kids imitate, lawyers panic.

And it’s rarely the biz that moves us forward; it’s the underground – the kids, weirdos, and bedroom producers playing with emerging technology – who drive change. JDilla had his MPC60. Brian Eno had generative music. Ghostwriter had retrieval-based voice-conversion (“RVC”) models. The industry fights what the underground proves already works.

If you’ve ever tried to do anything interesting with music, you’ve met its favorite “L-word”: licensing. You can’t press a vinyl, remix a track, or stream a boyfriend ASMR audiobook without it. Copyright law, as we know it, was practically written by musicians (or their lawyers) trying to get paid. The player piano birthed the first mechanical license. Sampling gave us fair use doctrine. Streaming resurrected performance rights in disguise.

Music doesn’t just follow the law – it teaches it.

So when born-digital art museum Rhizome and American art collective MSCHF invited us to make a little sumth’n sumth’n for this year’s 7x7 Program under the theme Law as Code, the prompt felt eerily familiar. Music has always been law as code. File formats and lawsuits share a syntax. Contracts are just metadata for meaning.

My collaborator and co-conspirator was Spencer Harrison of PleasrDAO, the internet collective that now holds Once Upon a Time in Shaolin – the single-copy Wu-Tang album so valuable and so restricted it can’t be played publicly until 2103. Recorded in secret from 2007 to 2013, it was RZA and Cilvaringz’s statement on the “cheapening” of music in the internet age. There was only one copy of the album ever created, with no (legal) access on streaming platforms. When Martin Shkreli (the controversial pharma-bro) bought it, it became a meme of greed. When the Department of Justice seized it, it became lore. When PleasrDAO acquired it, it became somewhere between museum piece and hostage.

To this day, it’s the most expensive piece of music ever sold. The liner notes read like scripture: for eighty-eight years, the holder may play it privately, free of charge, but never use it commercially or publicly. A perfect paradox: an album that exists to be heard, legally forbidden from being heard.

So that was our canvas.

2.0 Law as Code

When we kicked off our creative sprint, we asked: what if we made something from the restriction itself? What if the contract was the instrument?

Our answer became 1-800-SHAOLIN – a physical New York City phone booth turned audio confessional. A ritual you could dial into. Call the number, and the album calls back. No MP3s, no leaks, no downloads. We weren’t breaking the rule; we were performing it. If the law says “private listening only,” then we made privacy public. The booth became a temple. The call became communion. Just a voice on the other end of the line, whispering through the loophole.

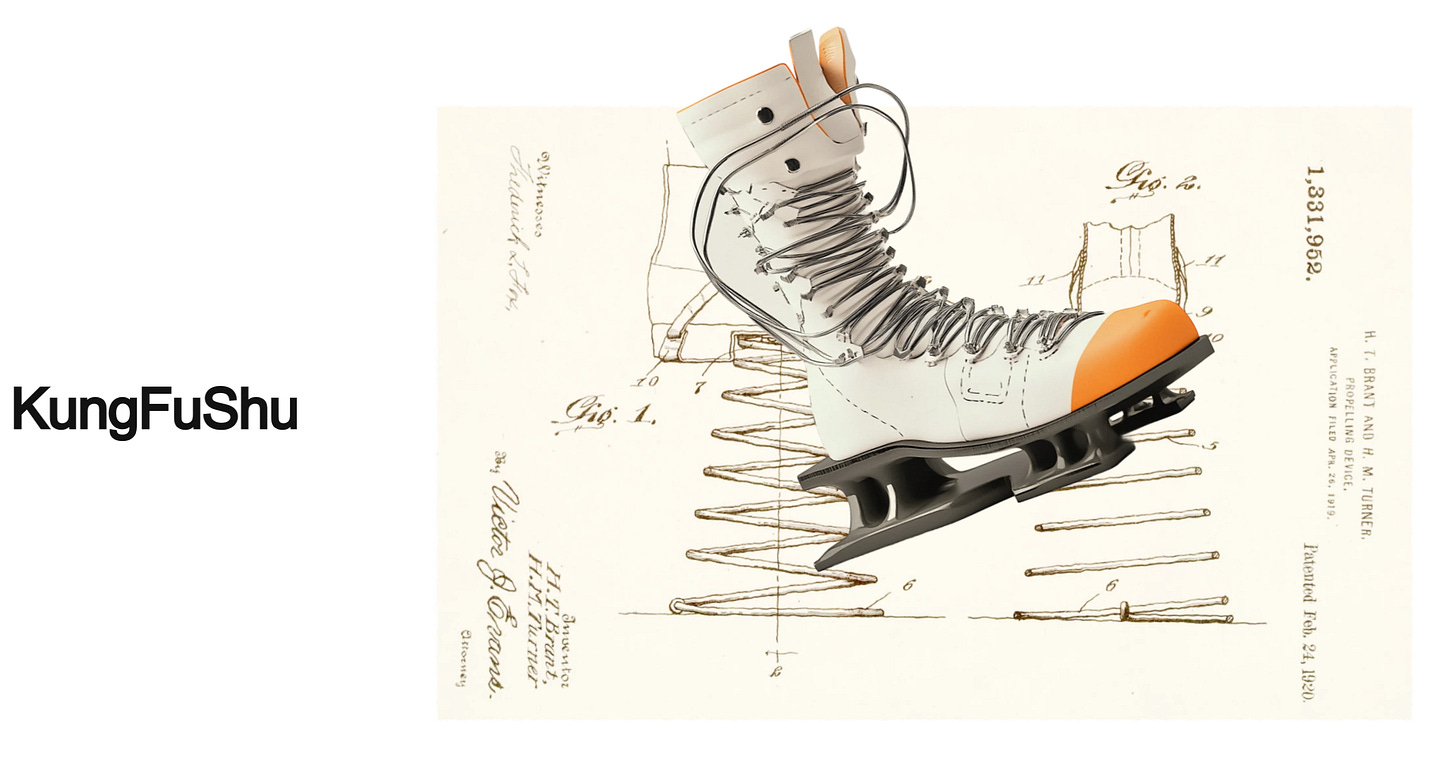

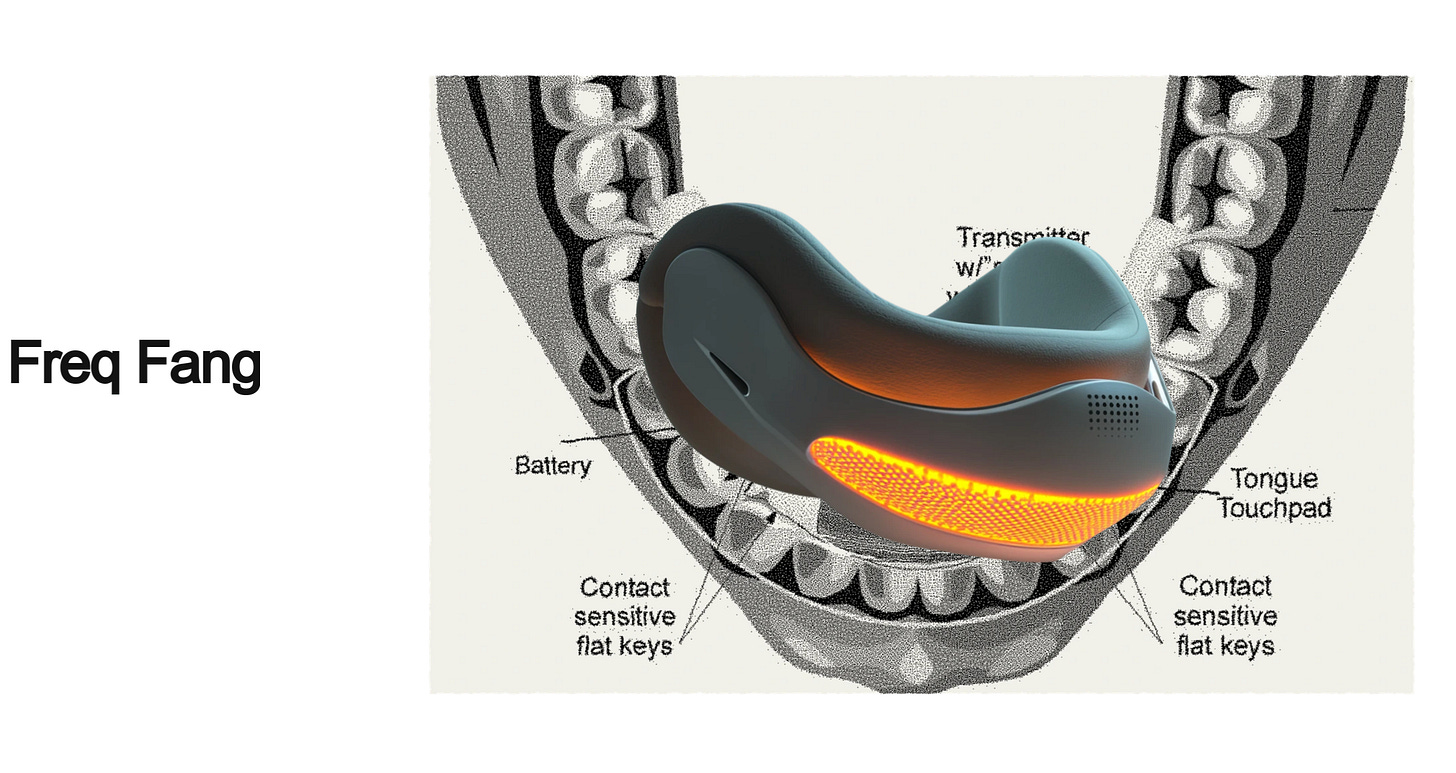

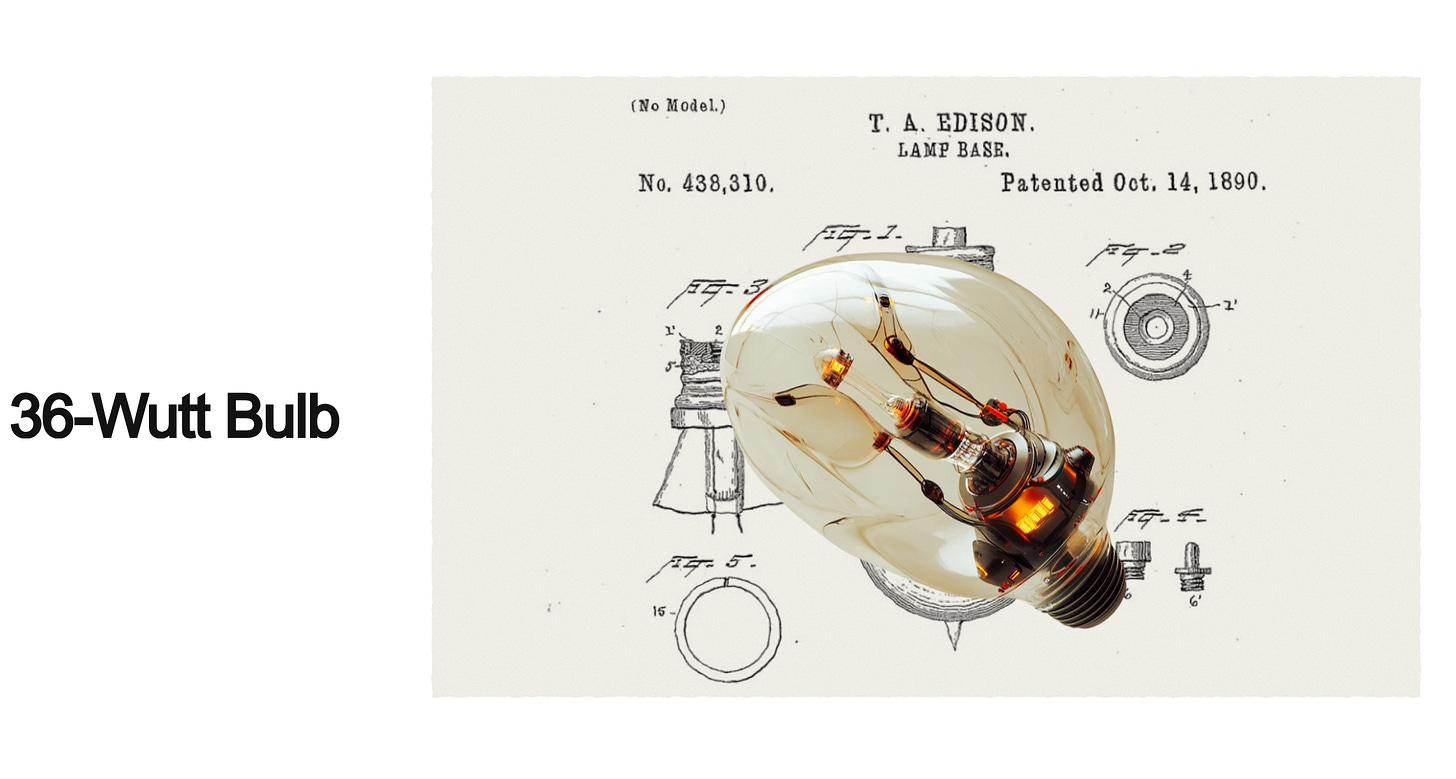

We also built a companion website where we stole – sorry, borrowed – intellectual property straight from the U.S. Trademark Office. We remixed filings into speculative listening devices: The KungFuShu: spring-loaded sub wu-fers that you feel in your (shoe) sole. Freq Fang: custom-molded mouth prosthetic for direct and personal vibration of the bones. 36-Wutt Bulb: sonic distribution via lightwaves and heat. Beatburger: an edible album. Half satire, half futurism. We were testing what happens when the machinery of law becomes a creative material.

And because we like to commit to the bit, we made the entire audience sign an absurd 300+ page NDA before the 7x7 presentation. A performative clause. A wink to the system. It turned participation into possession.

Music was never a product; it was always a verb. Musicking, as Christopher Small called it: the act of taking part, in any capacity, in a musical performance. Playing, listening, vibrating, translating. Even obeying the law could be a kind of musicking, if you do it with intent. So 1-800-SHAOLIN wasn’t just a creative project; it was a living test case. How far could you stretch legality before it turned into art itself? Could a contract become choreography? Could a clause have rhythm?

We learned that the line between art and compliance is paper thin. That law is just code in fancy clothes. That sometimes the only way to keep a song alive is to hide it.

(click above to watch the full presentation)

3.0 Code as Art

If Shaolin was a contract pretending to be an album, 1-800-SHAOLIN was an album pretending to be a contract. It lived in that thin space between compliance and creativity.

To me, that’s the takeaway: the boundary between the legal, the technical, and the musical keeps collapsing over time with every new emerging technology. I’ve spent years chasing that collapse – from my early days remixing music on a cracked copy of ProTools, to my last startup, Bubbl, a pre-TikTok video remixing app, to my recent explorations in AI-assisted creative. Whatever the era, I always land on the same tension: the gray area of legality, creativity, authorship, ownership, and play.

To its credit, music is still where the future shows up first. It’s where law gets rewritten in real time. It’s where technology learns how to feel culture. That’s why I spend most of my time here.

4.0 The Remix Clause

Throughout most of my work, there’s been an underlying obsession with remixing – the original term for “fucking with formats.” Bubbl. My website. Everything else I’m not telling you about (yet). Treating the component parts – the codes, the rules, the ingredients – as Legos is where I often find magic. But I don’t do it just to rebel, or to break the rules; I do it to create something fresh, and new.

Similarly, the point of 1-800-SHAOLIN wasn’t to break rules; it was to play them like instruments. Law is just code with a wig and robe on. Code is just law that goes

“beep boop” inside computers. Music is just law, code, and rules that we learned to play differently. Spencer and I did our best to apply that spirit of play to the rule of law and code itself.

Looking ahead, the next wave of creative work – especially with AI – will depend on how well we can translate between those systems: how we turn constraints into creativity, how we build new rituals out of regulation, how we adopt the spirit of music, and play, in our practice.

We’re all still negotiating what counts as creation. Maybe that’s the point. Every generation gets its own gray area to play in.

If it isn’t obvious yet, my POV is that we should do so freely.

Trust me, I’m a lawyer.

[Signature Page Follows]

/m, esq.